by Jen Lomberk, Matanzas Riverkeeper, on behalf of Waterkeeper Florida

In recent weeks, you may have seen articles about “WOTUS” or “Waters of the United States.” The argument over what does, and does not, constitute WOTUS has been around for almost 50 years – as long as the Clean Water Act has been on the books. In this blog, we will provide some background about the WOTUS rule and what it means for the waterways in our community.

WOTUS Woes

The Clean Water Act (CWA) was passed in 1972 with an objective to restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation's waters. The CWA seeks to achieve that objective through several programs, including requiring permits for the discharge of pollution into waterways, providing protections for wetlands, and directing states to set water quality standards and create restoration plans to meet those standards. However, for as long as the CWA has been on the books, there has been disagreement about which waterways do and do not receive the protections offered by the Act. The Clean Water Act applies to “navigable waters,” which are defined as the “Waters of the United States.” In other words, the protections offered by the CWA only apply to “Waters of the United States.”

For decades, regulated industries argued for a narrow definition of WOTUS - in order to limit the scope of the Clean Water Act, while environmental groups argued for a broad definition of WOTUS - in order to expand the protections offered by the Clean Water Act. After decades of confusion and litigation, in 2015, the Obama administration adopted the “Clean Water Rule” in an attempt to clearly define WOTUS, but that rule was challenged in court and repealed in 2019. In 2020, the Trump administration adopted the Navigable Waters Protection Rule, a considerably narrower definition of WOTUS, but that rule was similarly challenged in court and repealed in 2021. In an attempt to create an enduring WOTUS rule, early this year, the Biden administration adopted the "Revised Definition of 'Waters of the United States'" rule, which is generally considered more protective than the Navigable Waters Protection Rule, but less protective than the 2015 Clean Water Rule. Soon after its implementation, this rule was blocked in 24 states (including Florida) by a federal district court in North Dakota, prolonging the confusion about the scope of the Clean Water Act.

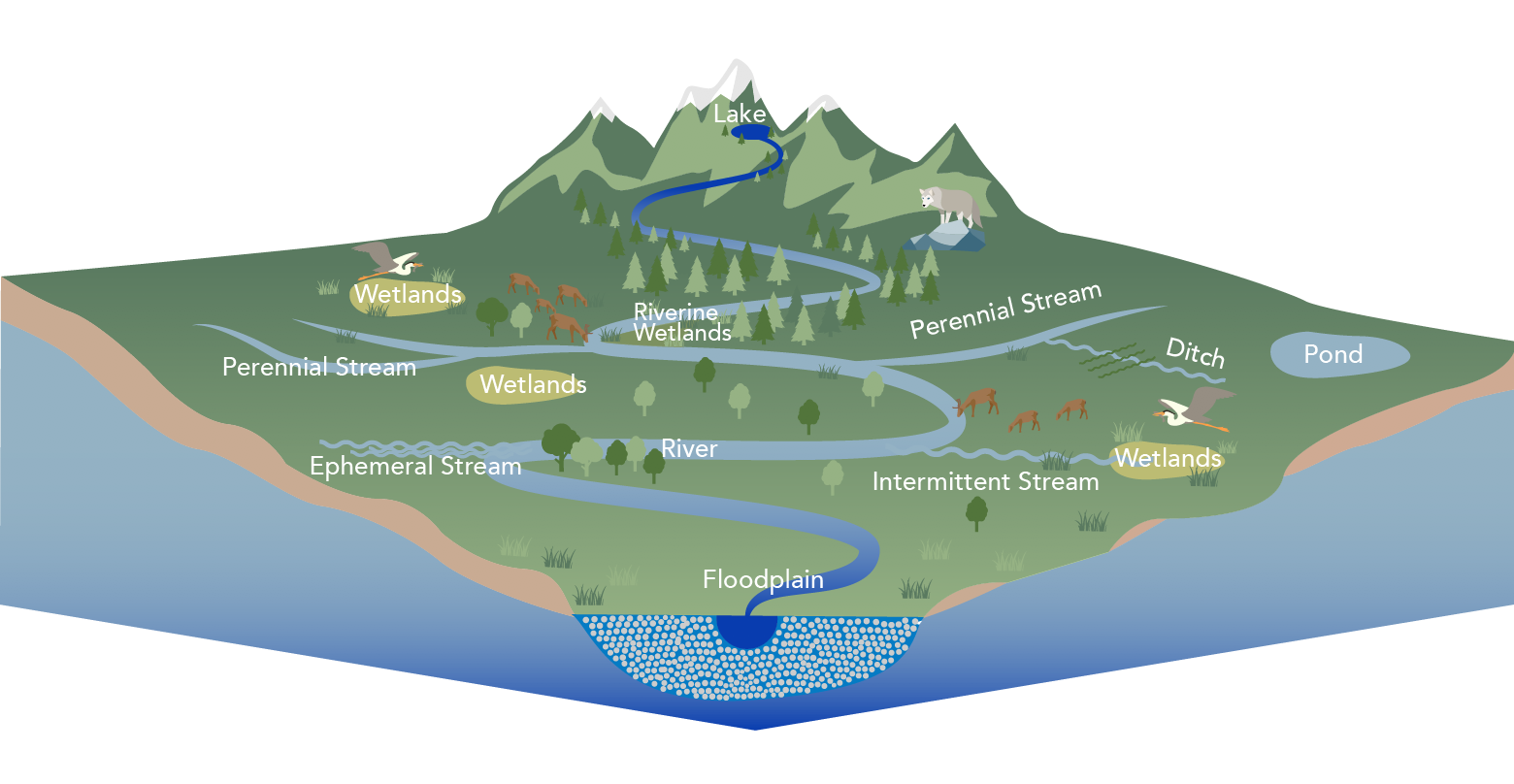

The differences between the rules are often focused on which wetlands are covered by the CWA and whether ephemeral waterways - rain-dependent streams that flow only after precipitation - are protected by the Act.

Wetlands 101

Florida contains more wetland area than any other state in the continental United States, but it is estimated that Florida has lost 9.3 million acres of its wetlands or approximately half of its historical coverage.

Despite their prevalence in the Florida landscape, wetlands are an under-appreciated ecosystem. Wetlands serve water quality filtration functions, aquifer recharge, and provide habitat as well as flood water retention, which is obviously critically important in South Florida, where we are dealing with increasing flood events and water quality issues. The health of wetlands also impacts larger waterbodies to which they are hydrologically connected.

When wetlands are included within the definition of WOTUS and protected by the Clean Water Act, developers are required to obtain a permit before filling in wetlands and are subject to regulations that protect wetlands. If a wetland is not covered by the definition of WOTUS, then it will not be protected by the Clean Water Act and can be legally damaged or destroyed, regardless of the broader water quality impacts.

SCOTUS on WOTUS

As if the back-and-forth about the definition of WOTUS wasn’t confusing enough, the looming Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) decision in Sackett v. EPA threatens to muddy the waters even further (pun totally intended). The Sacketts, Idaho landowners, brought this lawsuit backed by polluting industries in an attempt to limit the reach of the Clean Water Act. In 2007, the couple purchased property near Priest Lake, one of the largest lakes in Idaho. EPA told them that they were required to obtain a wetland permit before developing it. Instead of obtaining the permit, the Sacketts brought a lawsuit claiming that the EPA does not have the jurisdiction to regulate the wetland on their property, kicking off a legal battle that has spanned well over a decade. While on its face, this might seem like an argument over a single piece of land, this case could actually have enormous impacts on waterways across the country. This lawsuit was designed by industry polluters specifically to undermine Clean Water Act protections. The Supreme Court’s decision is due any day now and could dramatically change EPA’s authority to enforce the Clean Water Act.

Locals Leading

Due to the immense confusion about wetlands protections at the state and federal levels, many local governments have stepped up and adopted local regulations to protect their wetlands. By adopting these protections, local governments are working to ensure that the valuable ecosystem services that are provided by wetlands remain in their communities. However, new laws backed by industry polluters threaten to limit the power of local governments to protect their wetlands and other natural resources.

What’s Next for WOTUS?

As we await the decision in the Sackett case, we anticipate that the fight over the Waters of the United States is far from over. As Waterkeepers, we will continue to work to defend the integrity of the Clean Water Act and the waterways and communities that it protects.